Reading Law Moves Toward Retention

Incoming third graders next fall will be the first group whose spring test scores will be used to determine if they move on to fourth grade or not, under requirements of the third grade reading law passed by state lawmakers in 2016.

Many questions remain about how the law’s mandates will work in practice.

One looming issue surrounds the state’s standardized assessment for third graders, M-STEP, which does not determine a child’s reading level by grade. Instead, results come in the form of one of four labels from “not proficient” to “advanced.”

Meanwhile, the law requires students who test “one year or more” behind grade level to be retained in third grade. School districts are awaiting guidance from the Michigan Department of Education to clarify how to determine which students are “one year or more” behind.

In addition, the law allows for exemptions from retention, but students who advance to fourth grade through one of the loopholes will have to spend a greater portion of their day in literacy activities—calling into question what changes will happen to fourth-grade classrooms in 2020.

Now in its third year of implementation, the law has been viewed by many educators as heavy on paperwork and mandates and light on funding and resources.

In a recent statewide survey of educators, one-quarter said their district is not prepared to provide support to retained students. That number rises to 40 percent in high-poverty urban districts with low per-pupil spending.

Requirements to test, diagnose, and write Individual Reading Improvement Plans (IRIPs) three times per year for every K-3 child deemed “deficient” have drained time away from teaching and intervention—especially in areas with too-large class sizes, educators say.

Fewer than half of the state’s third graders scored proficient or above last spring on the M-STEP English Language Arts assessment, which replaced the Michigan Educational Assessment Program (MEAP) in 2015.

MEA lobbyist Dr. David Michelson spent several months last year gathering feedback on the law’s implementation from members who participated in focus groups across the state. MEA member recommendations have been shared with lawmakers in an effort to improve the law.

Those include ideas such as not requiring IRIPs for special education students who already have Individualized Education Plans (IEPs); not requiring testing in kindergarten; establishing caseload guidelines for literacy coaches; and providing paid time for teachers to complete IRIPs.

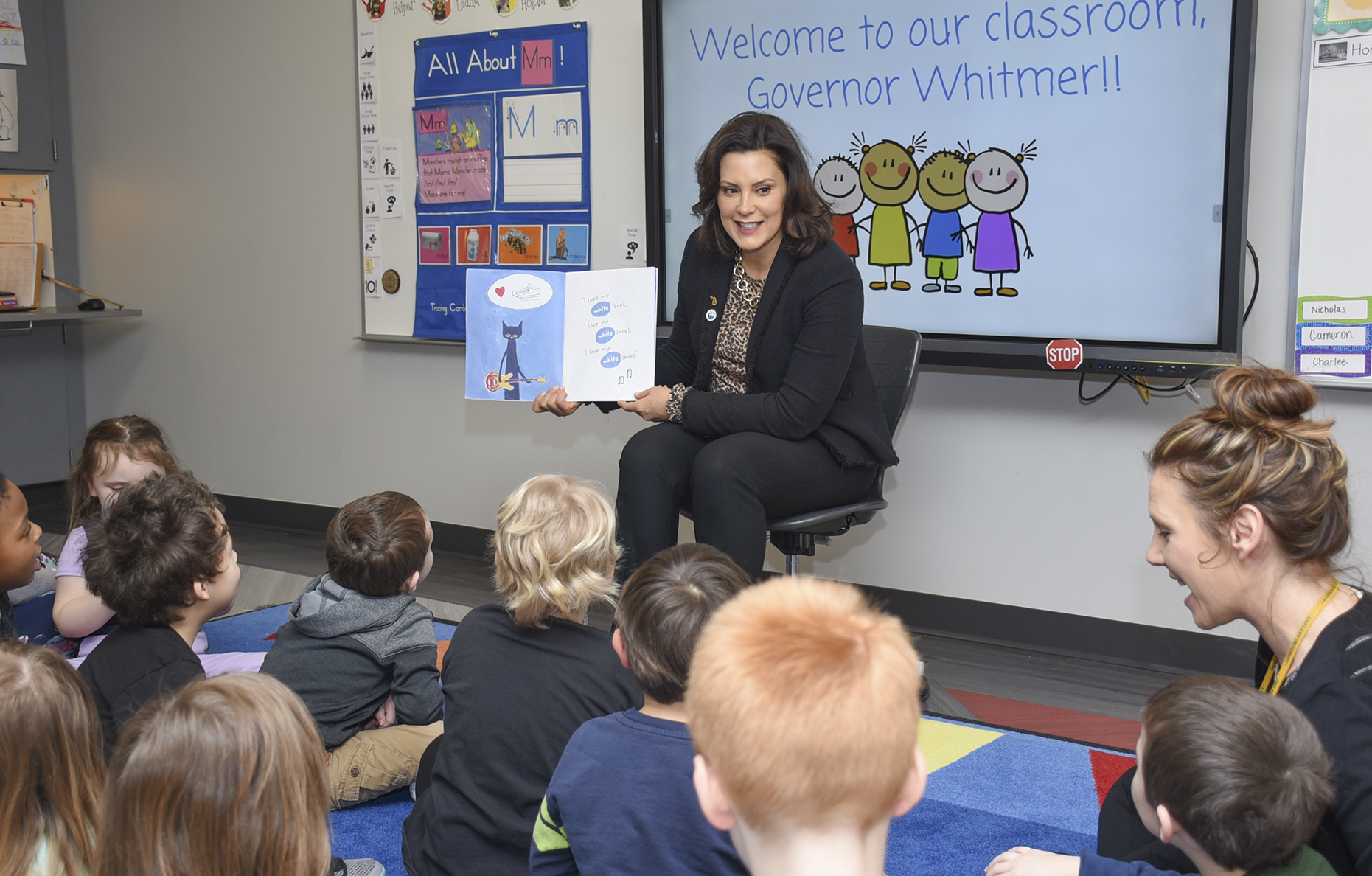

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has taken a different approach to addressing literacy in the state. Her proposed budget includes boosting overall education spending with a per-pupil funding increase; adding funding to pay for more literacy coaches statewide; and providing additional funds for schools with higher numbers of at-risk students.

In a recent M-Live Citizen Roundtable, Whitmer called the third grade reading law “destructive” and questioned the retention policy. Research shows that holding children back does not improve outcomes later in their schooling.

“A child who can’t read isn’t going to become a better reader because you told them that they’re bad or you penalize them,” Whitmer said. “Their parents aren’t going to get more engaged because you made their child pay a penalty for not reading.”

Stay tuned for updates on possible changes to the law or further guidance on implementation in MEA’s e-newsletters, MEA Voice Online and Capitol Comments. Sign up to receive them at mea.org/signup.